Third dialogue:

Data sharing: The promises and perils of open and shared data

Data sharing is the third and next stop on the Road to Bern, following our dialogues on data collection (19 February 2020) and data protection (22 and 23 April 2020). This briefing note provides background points for our discussion on data sharing, which will be held on 26 May 2020.

Data sharing is of profound importance for common and evidence-based policy-making and global governance as well as vital for attaining the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in a holistic and an impactful way.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which shook our economies and social systems to the core, only further accentuated the relevance of data sharing for international cooperation. And yet, although data sharing is frequently proclaimed an important goal, it is only advanced occasionally in international co-operation. While it is stipulated as a core principle in more than 30 international declarations on data governance, in practice it is not always treated as such.

What is the missing link? What can be done to close the gap between proclaimed principles and reality of data sharing? How to identify, exchange, and use data across the data silos?

These and other questions on data sharing will be discussed through a variety of experiences and approaches during the next Road to Bern dialogue.

Discussions on data sharing have so far converged around the UN’s experience in New York, host to the UN Global Pulse, the UN Statistical Commission, and three major initiatives on data and global cooperation associated with the UN Foundation in New York: the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, Data 2X, and the Digital Impact Alliance.

Our discussion will contribute to the global knowledge on data sharing by harvesting Geneva’s diverse and rich experience and expertise ranging from the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) which has open data access as its core institutional principle, via the International Trade Center (ITC) which supports better access to data as a basis for inclusive trade and economy, to humanitarian organisations which have a more restrictive approach to data sharing given that misuse of data may endanger the lives of the people they protect.

The Road to Bern discussion will focus on several pillars of data sharing.

Identifying the purpose of data sharing is one of the most frequently quoted principles for dealing with sensitive data. As an example, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) shares data with other agencies only when people they care for can benefit from shared data, and if the goal is humanitarian. Data is shared once a Privacy Impact Assessment confirms these criteria. However, a narrow view of this principle may lead us to overlook incidental insights, patterns, and correlations.

The standardisation and harmonisation of data is essential as new and diverse data sources emerge. The diversity of data types and sources is particularly important for ensuring data sharing across the 230 SDG indicators. There are also a growing number of sectoral initiatives which develop standards and other measures promoting harmonised data, such as trade facilitation (UN Centre for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business), meteorology and hydrology (World Meteorological Organization), and the humanitarian field (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ (OCHA) Humanitarian Data Exchange).

The standardisation process of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), for example, breaks down silos by involving various industries, regulators, and academic institutions into the process.

Data protection and security are particularly important in the humanitarian field, where the mishandling or misuse of personal data can have serious consequences to people’s safety. Regardless of the field and scope, the sharing of data should adhere to national and international regulations, standards, and principles. A number of data collection and processing principles have been developed by major international organisations and other actors. Anonymisation, coupled with technical and legal measures to minimise the risk of de-anonymisation, is one approach for sharing aggregated personal data, especially during crises such as COVID-19.

Private-public partnerships are emerging as a key pillar of data sharing, in particular, between tech companies which collect large amounts of data, and international organisations and governments which require data for effective public policy. The COVID-19 pandemic increased private-public cooperation around data, especially on epidemiologic measures, research on vaccine and health solutions, and the use of contact-tracing apps for social distancing and preventing spread of virus.

One of the first examples of effective private-public partnerships was the use of phone data during the Ebola epidemic. Since then, mobile network operators have been important data contributors health protection, education, and financial inclusion.

At the international level, there have been few initiatives. The mobile industry association GSMA introduced a wide range of principles and guidelines for data sharing between companies and the public sector/international organisations such as GSMA’s Big Data for Social Good (in co-operation with the UN Foundation) and, more recently, GSMA’s COVID-19 Privacy Guidelines. On the other hand, the Global Initiative on AI and Data Commons aims to bring together data owners from different stakeholder groups. Additionally, the International Trade Centre (ITC) has been cooperating with Alibaba and using their data to measure the inclusion of the least developed countries (LDCs) in the global e-commerce market, and to categories products which are traded worldwide.

With an increasing number of data protection regulations, data sharing faces administrative and legal complexities. International organisations can address this challenge by having a co-ordinated approach in negotiating data-sharing arrangements with the private sector, academia, and other stakeholders. An example is the UN Global Pulse’s support to the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) to establish a legal arrangement with Twitter for using the company’s datasets for anti-discrimination campaigns.

The alignment of incentives among international organisations, companies, and governments, is a pre-condition for effective partnerships around data-sharing. At present, the incentives and motivation of major actors are very diverse. Pressured by financial austerity measures, international organisations and national governments may use data they produce or manage as a potential source of funding. This is why it is crucial to ensure that data sharing does not become collateral damage of various budgetary cuts and restrictions.

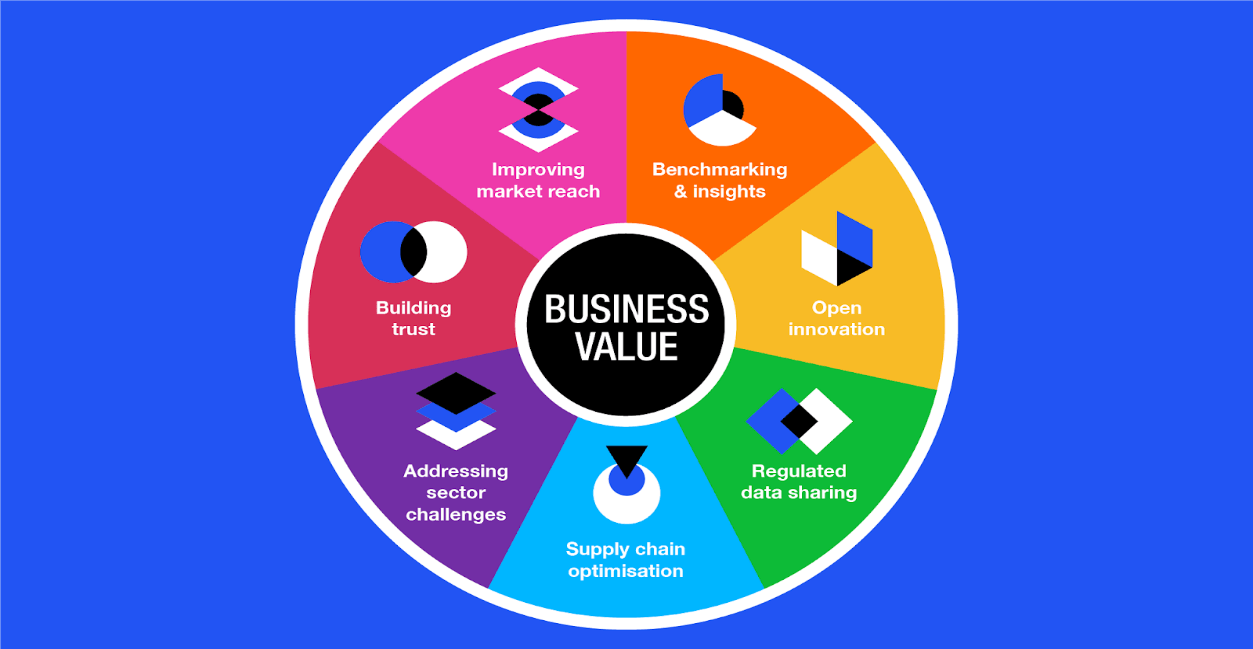

With regard to incentives for the private sector, The Open Data Institute (ODI) has identified seven categories of generating value through data sharing (see illustration). Read a detailed analysis of each of the seven categories.

Data commons, public goods, and related concepts

In the policy field, data is increasingly being considered under a few legal and policy concepts, such as data commons, public goods, and the common heritage of mankind. For example, the UK National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) published the report ‘Data for the Public Good’ where it addressed, among others, the benefits of having information available to the public in various contexts, ranging from the environment to everyday activities such as reducing time spent in traffic.

CERN, as one of the leading organisations in providing global public goods, shared its experience during the event co-hosted by CERN and the UN titled ‘UN and Global Public Goods’. In its article ‘Let’s make private data into a public good’, the MIT Technology Review calls for a substantive change of the current business model based on the monetisation of personal data. Data received a central position in Malta’s proposal for the Internet as a common heritage of mankind. Technically speaking, data which is not personal can be both non-excludable (anyone can access it) and non-rivalrous (access by one person does not diminish its value for others). However, when it is used and managed, data acquires the mixed characteristics of exclusivity and rivalry as summarised in the following table.

| Rivalrous | Non-rivalrous | |

| Excludable | Personal data is in the focus of policy debates since the introduction of the GDPR and other data protection regulations worldwide. The monetisation of personal data by tech companies turns it into private-commercial data. The bulk of policy debates are related to the use, protection, and management of personal data. | Community and cloud data is generated by cities and local communities. For example, there are policy discussions whether data provided by cities should be considered open data or data that should benefit only citizens of a particular city/region, or members of the communities that generated the data. |

| Non-excludable | Open data – commercial use Data is accessed freely, but once it is used for specific purposes, it may become rivalrous on the market as part of a product or application. | Open data – public use Data generated by publicly-sponsored projects (CERN – scientific data, meteorological data, etc.) |

The way forward

In harvesting the experience of Geneva-based organisations, our next discussion on the Road to Bern will advance the search for a win-win solution on data sharing. This solution should not only be inspired by the core values of international cooperation, but also anchored in the practical policy and budgetary reality of international organisations, tech companies, countries and communities worldwide. See you on Tuesday (26th May).